Nested Hierarchies: Whiteness, Europeanness, Russianness, and their Others

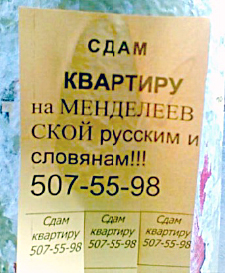

A street advertisement that reads “An apartment for rent on Mendeleev Street. Russians and Slavs only.” (The word Slavs is misspelled: “Slovs” instead of Slavs)

Relevant Articles

- David Crowley, “Seeing Japan, Imagining Poland: Polish Art and the Russo-Japanese War.” The Russian Review 67, no. 1 (2008): 50-69.

- Hilary Pilkington, “No Longer “On Parade”: Style and the Performance of Skinhead in the Russian Far North.” The Russian Review 69, no. 2 (2010): 187-209.

- John W. Slocum, “Who, and When, Were the Inorodtsy? The Evolution of the Category of "Aliens" in Imperial Russia.” The Russian Review 57, no. 2 (1998): 173-90.

- J. Otto Pohl, The Russian Review 76, no. 3 (2017): 570-571.

Russia is unquestionably a global power. However, it not only aligns with trends established by other imperial powers, but it also diverges from them. By delineating these convergences with dominant global power structures, on the one hand, and identifying specifically Russian exertions of power, categorization, and policies on difference on the other, we can trace how power and race are intertwined without losing view of the specific qualities of Russia’s historical context.

In his article from 2008, David Crowley reminds us that when the Russian Empire took the mantle of defender of Europe against the so-called “yellow races” during the Russo-Japanese War, not all Russian imperial subjects aligned themselves with this move. A segment of the Polish population identified with the Japanese, emphasizing their shared experience of resistance against the pressure of Russian imperialism. Oppression in this case gave rise to solidarity.

Ironically, this identification ignored the similarities between Russia and Japan as empires. Crowley intimates that similarities between the Russian and the Japanese imperial projects were more evident to educated Poles who were in exile in the Far East or served the Russian Empire there. Many gained firsthand experience of Japan and the diverse peoples under Japanese rule and came to sympathize with them as victims of Japanese imperialism and violence. While these sympathies and solidarities were not expressed consistently, they demonstrated that imperial subalterns could and did find affinity with other oppressed groups – be it in Russia or elsewhere.

In her article from 2010, Hilary Pilkington invites us to approach whiteness in relation to the skinhead subculture in a town in Russia’s Far North. As Pilkington asserts, viewing skinheads in Russia as simply mimicking “the West” is inadequate. Russian skinheads do not merely take on pre-coded symbols, styles, and embodiments of whiteness from abroad. Therefore, scholars need to pay attention to the ways that specific communities in Russia negotiate and reflect upon their involvement with skinhead forms and styles.

Pilkington pursues this task by focusing on how her interlocutors rely on performative style, which is instrumental in understanding shifts in meaning among symbols, ideas, and actions as the community’s markers changed. As a result, race and racial alignment emerge as a highly contextual and localized phenomenon despite their globalized representations.

Considering Jon K. Chang’s Burnt by the Sun: The Koreans of the Russian Far East in his 2017 book review, Otto Pohl foregrounds racialization and racism as significant parts of the Soviet Korean experience. Chang traces continuities between Russian imperial and Soviet racial prejudices against Koreans and others. Pohl emphasizes that Chang’s argument goes against the view of many historians who insist that racism was not a systemic feature of Soviet nationalities policy. Pohl praises Chang’s work as an example of the type of research on the Soviet Union that needs to be conducted more often.

Finally, John W. Slocum, writing in 1998, analyzes the legal category of inorodtsy from 1822 to 1917. Often translated as “aliens” or “foreigners,” the term inorodtsy (literally “people of a different kin”) originally referred to Siberian Indigenous peoples and became codified in law in 1822. As Slocum points out, the inorodtsy “were a clearly enumerated and delimited set of peoples not subject to the general laws of the empire, who preserved their local customs and traditional leadership and enjoyed certain other privileges, most notably exemption from military conscription” (Slocum 1998, 173). Over the course of the nineteenth century this juridical category entered common parlance and was used to refer to all non-Russians.

As the empire expanded, imperial officials were required to categorize the peoples of newly acquired lands, many of them nomads. However, Jews were legally considered inorodtsy beginning in 1835, revealing the category’s instability, since most Jews lived settled lives largely confined to Eastern European territories incorporated into the Russian Empire in the previous century. Slocum demonstrates how non-Jewish inorodtsy – mostly nomadic and semi-nomadic pastoralists and hunters of Siberia – were intended to be transformed into settled agriculturalists, which theoretically would have removed the need for the legal category.

Such a policy was strikingly similar to other assimilationist projects that targeted Indigenous peoples around the world and sought to “civilize” them by transforming their way of life. However, notions of immutability remained, preventing inorodtsy from becoming “regular” subjects of the Empire. Reflecting the salience of racialized categories in Russia, the difference between these groups and Russians was at times described as being determined by biology and “blood” (Slocum 1998, 186-7).